A Prairie gothic

Heather Benning: A Prairie Gothic was organized by the Moose Jaw Museum & Art Gallery.

Curated by Jennifer McRorie

A Prairie gothic: let our fields be broader, but our nights so much darker

Written by: Ross Melanson

With her gallery-‐based installation, A Prairie Gothic: Let Our Fields Be Broader, But Our Nights So Much Darker, Saskatchewan artist Heather Benning creates a powerful evocative space that is poetic; rich with allusion and imagination. This ambitious body of work is constructive in nature and seeks, ultimately, to create a warm, enriching human experience that is more sublime than cognitive. Its use of visceral tableaus and cinematic imagery accomplish an empathetic gaze in the viewer and, ultimately, produces a transcendence of the ordinary and a plea for human transformation.

The name of this exhibition not only belies its poetic nature it provides access points for the work it denotes. It associates the content of the installation with the Gothic tradition emerging from the medieval period. Given the paraphrased quote emerging from Thoreau’s essay on walking, the title also associates the content with the transcendentalists of early America.

Benning’s first significant exposure to Gothic art came in the form of the architecture she encountered during her education at the Edinburgh College of Art in Scotland. Two of the pieces included in this exhibition (The Altar and Larry and Rosalie) find their aesthetic origins in direct reference to this encounter. However, Benning’s Gothic impulse is philosophically-‐driven and comprehensive, making her expressions significantly more than a superficial visual reference to an historic aesthetic.

Gothic tendencies emerged from a complex philosophical angst within the medieval era and travels through variant expressions in visual art, literature, and film to the modern era.1 Generally speaking, Gothic thinking challenges all forms of classicism which deny any authority to subjective human experience in order to accomplish an objective, conceptual and rational basis for truth or self-‐understanding. In contrast, Gothic thinking takes a more subjective, poetic and narrative approach that often uses heroic, cataclysmic, magical and mythic narratives that can only be accessed through the suspension of disbelief.

In its more recent manifestations, the Gothic aesthetic leans on gramarye2 and horror3 in order to shock the viewer from their cold, detached and objective rationalist thinking in order to make individuals realize the actuality of their subjectivity within the physical world.

Fundamental to Gothic and transcendentalist thinking is the realization of an authentic self freed from the austere, detached and dogmatic prescriptions of rationalist self-‐understanding. The foundational pedagogic and prescriptive intentions of the Gothic aesthetic circles around a representation of an idealized, culturally compromised self that is “exaggerated and repudiated, explored and denied by Gothic sensibilities.”4

Overall, Benning employs many traditional Gothic affective tropes. She utilizes images that are both familiar and evocative to engage the emotions over the mind. Her images are often grounded in poetic, poignant, highly-‐charged elements of everyday life rich with meaning and memory: family; childhood homes; objects of childhood play; and religious objects like altars or sarcophagi. Her expressions also contain various shades of the horrific and macabre which is so prevalent in Gothic expressions: the systematic oppression of young girls in the educational system; the notion of the inevitable death of her parents; and a historical narrative of a cataclysmic relationship ending in a grotesque murder. Her reference to the memorialization of martyred saints using pictorial narrative and monuments parallels the Gothic attraction to the heroic, mythological and supernatural narratives. Canonized saints, after all, must be associated with at least two miracles after their death.

Benning not only utilizes tropes associated with traditional Gothic sensibilities, her work also centers around its primary agenda – exposing and negating the culturally conformed self. Benning works in favour of a more authentic and emancipated self. While doing so, she contextualizes the Gothic tradition within her modern, rural, Saskatchewan experience. The result is a sophisticated prairie Gothic with its own aesthetic guides for approach and content. Drawing on specific cultural aspects of rural prairie history and life, Benning creates genuine felt experiences in the viewer which she then funnels into an imaginative gaze .

A Prairie Gothic: Let Our Fields Be Broader, But Our Nights So Much Darker is a realization of Benning’s original vision to exhibit The Altar, Larry and Rosalie, and Work hard, be nice together. These three tableaus situate the viewer before them, providing a scene or situation that demands an empathetic gaze.

The Altar finds its aesthetic inspiration in direct relation to the medieval altars Benning encountered in Scotland. These free-‐standing altars were decorated with sacred images to evoke spiritual devotion from those who contemplated and worshipped before them. Typically, these images conveyed grisly stories of martyred saints, using their intense and ideal devotion as an inspirational model for spiritual dedication. In Benning’s hands, however, the altar conveys the true and horrific story of an estranged immigrant couple who come to tragic ends. This piece, shaped like a grain elevator and made from humble and earthy materials like chipboard, cedar and pine, presents Benning’s imagined explanation of how a young loving couple, who begin a hopeful life together in a new land, ends in contempt and murder. This piece manifests Benning’s empathetic gaze which models the engaged consideration of understanding while resisting an approach of detached judgement and mere assessment of guilt.

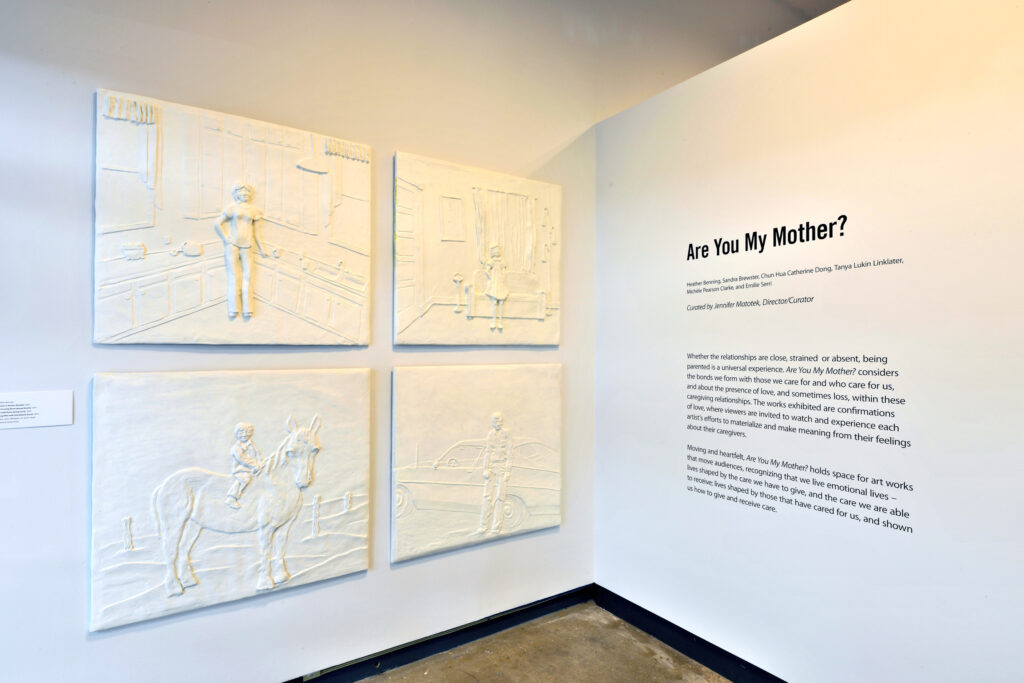

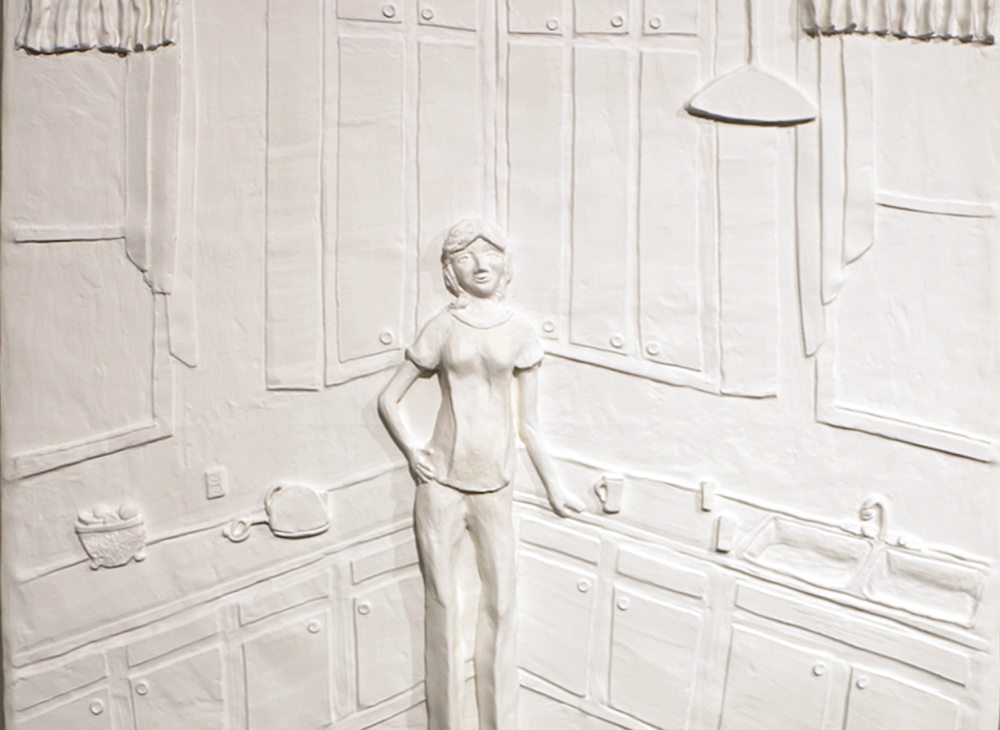

Larry and Rosalie, along with four related biographical story panels, creates another tableau pulling on the metaphor of saints and drawing from Benning’s experience in Europe. These two sculpted works are made in the likeness of the artist’s parents and are given their names, presents a contemporary and regional reading of the sarcophagi populating European sanctuaries. Traditionally, sarcophagi presented idealized and stately images of nobility, knights and saints, presenting them as models of greatness and significant accomplishment. In contrast, Benning’s, morbid but venerate presentation of her living parents transforms the meaning of gallant sainthood, associating it with the notion of hard, common, and everyday work. Again, Benning’s empathetic gaze resists high and idealized notions of accomplishment and invests the ordinary with transcendent value.

Work hard, be nice keeps attention on oppressive and condescending social constructions of self-‐understanding while shifting its guiding metaphoric context from religion to education. It presents a third tableau of twenty-‐nine girl statues on the ground under a series of “wallflowers” and wedged between six statues of jaunty boys on pedestals. These figures, reminiscent of 1950s illustrations from educational readers like Fun with Dick and Jane, depict the oppressive nature of the educational aphorism that names it. The girl statues, with heads submissively bowed and hands gently clasped, fret about their “niceness” in a muddle at the viewer’s feet. The wallflower figures emerging from and then disappearing into the wall directly above them are idealized half-‐figures of passive women separated from the actuality of daily activity waiting for men to engage with, and thus validate, them. Flanking the fretting girls, extolled but innocent boys are venerated, without accomplishment, merely for being potential men.

The moral implications of this dark condition emerges, once again, from Benning’s empathetic gaze. The aesthetic indicator of this gaze is found in the fact that, though all these “girls” has been mass-‐produced by a single mold, they are the only figures in the tableau which have been given special and careful attention by Benning. Each of these figures is “humanized” by painting them into an individuated character. However, in order for the viewer to observe this in actuality, they must take the position of supplication and humility – kneeling and bowing

– in order to see these figures as actual individuals.

The two remaining pieces within this exhibition, The Dollhouse and Burn Pile I, have a documentary nature related to a previous benchmark work. In 2005, the artist accessed a farmhouse abandoned since the late 1960s. By 2007, she refurbished and furnished the house, transforming it into a life-‐size dollhouse.

Burn Pile I is a glossy, resin-‐coated, collage-‐based structure presenting images of abandoned and weathered houses in the prairie Gothic architectural style. Benning accumulated these images during preliminary research for Dollhouse. Its cryptic title refers to burning pits on farms in which detritus is collected and eventually purged by fire. The Dollhouse, is a highly-‐dramatized, haunting, documentation of the earlier work’s fiery destruction after 8 years of installation. A troubling audio track replete with squeaky swings, blowing winds and disquieting music, combined with rich and lonely images, create an emotive foreboding sense of the sinister and sense of impending doom reminiscent of the horror genre.

The site-‐specific Dollhouse was an arresting transformation of an ominous prairie icon.

It coincided two thematic metaphors -‐ childhood play and settler immigration – both of which are grounded on a highly imaginative state that supersedes realistic rational thinking and guides activity. Early prairie immigrants abandoned established and highly-‐developed cultural lives and moved to a harsh, undeveloped environment because they imagined themselves eventually having a better and self-‐directed life. Children, freed from an adult world saturated with rationalized pragmatism, apply imagination at will, animating and transforming most everything into play.

An apocalyptic air hovers over this entire exhibition and is made most clearly manifest in

these two documentary works with their metaphor of destructive fire. Benning’s poetic adaptation of Thoreau’s words within the exhibition title allude to her prophetic conviction that we have been severed from our spiritual grounding in an innocent imaginative past. Idyllic dreams of authentic autonomous independence have been transformed into a sinister, stark economic mandate to survive. As the model of the family farm is transformed in a corporate model of “big farming,” there is a consequent increase of physical separation and a darkening of the night. The fact of this darkening, Benning observes, is a poetic indication that our souls may be proportionally growing darker. The exhibition embodies the empathetic humble tone

and wanton imagination required for a more humane and enriching self-‐understanding.

1 For a more comprehensive understanding of the Gothic attitudes, especially during the mid–‐eighteenth century, read Richard Hurd’s Letters on Chivalry and Romance.

2 alternate belief systems that rely on supernatural aspects like engaging the dead and other occultist practices

3 narratives containing activities in which people are acting in ways that deny the civilized individual so idealized in

rationalist thinking.

4 Miles, Robert, The Gothic Aesthetic: The Gothic As Discourse Source: The Eighteenth Century, Vol. 32, No. 1 (SPRING 1991), pp. 39–‐57, p. 40

Heather Benning: A Prairie Gothic was organized by the Moose Jaw Museum & Art Gallery.

Curated by Jennifer McRorie

Copyright 2024 Heather Benning. All artwork and content (images and text) on the Heather Benning website are the sole property and copyright of Heather Benning and are protected by copyright laws.